Opened to the public late last year was the long awaited Victorian Books, ‘a Distant Reading of Victorian Publications.’ Working with data from Google Books, Dan Cohen and Fred Gibbs are text mining every book published in Britain in the long (meaning 1789 to 1914) nineteenth century. That’s 1,681,161 titles. And they’re releasing the data, not just the graphs showing the frequency of selected words, from ‘Agnosticism’ to ‘Worship’, but also the actual counts of 99 terms, in .xls (Microsoft Excel*) and .tsv (tab separated) formats.

Cohen’s specific historical object is the Victorian ‘frame of mind.’ How did they think, how did they see the world, and how did they believe? His method is to use Google’s vast digitization program to read the Victorians, or at least those who were published, en masse, rather than rely on a canon of notable authors. The move from the anecdotal and elite selection of Houghton’s The Victorian Frame of Mind, 1830-1870, to a truly comprehensive survey of all Victorian authors, will hopefully give a broader, more accurate and more subtle view of Victorian modes of thought, and perhaps a more open one that allows for discordance and diversity.

This isn’t a simple matter of chucking a load of material into a database, pushing a button and then having the computer throw out unambiguous facts and truths. Cohen and Gibbs have posted some caveats: the data isn’t perfect, meaning of words change over time, as yet only the titles of books are being mined, no collocation or context is given. It also requires some careful methodology, and weighing for all sorts of extraneous factors: William Briggs has done some very interesting analysis bringing in population statistics. But with freely available data, anyone with a spreadsheet program can try out ideas and run checks, allowing for the collaborative development of analytical techniques.

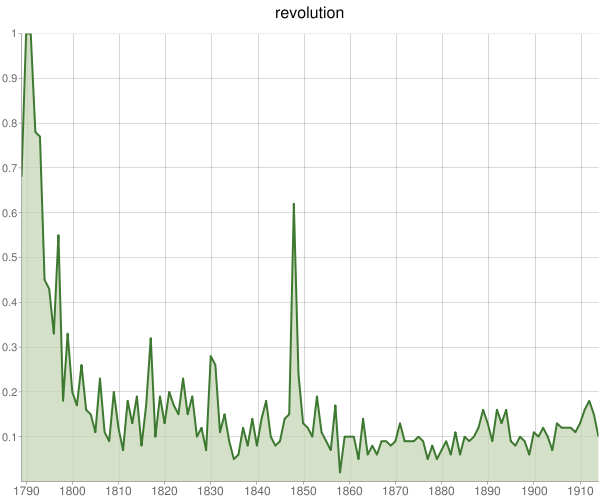

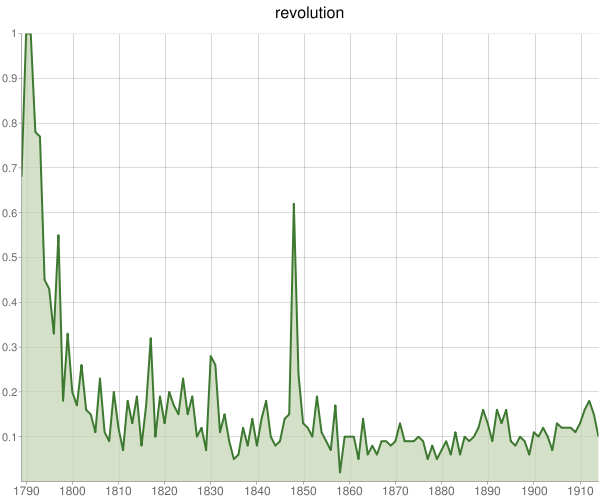

Percentage of British books with 'revolution' in the title, 1789-1914

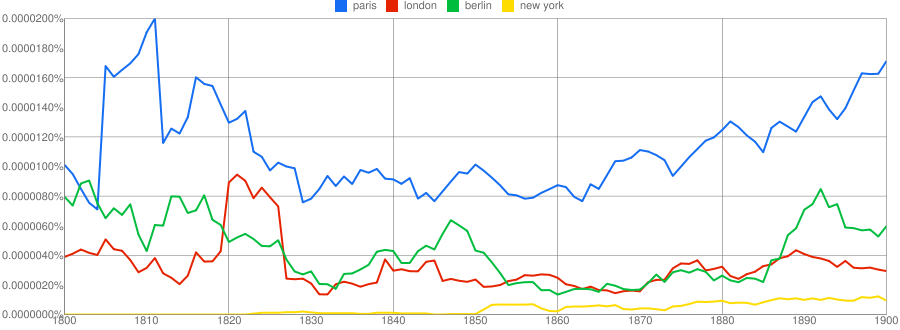

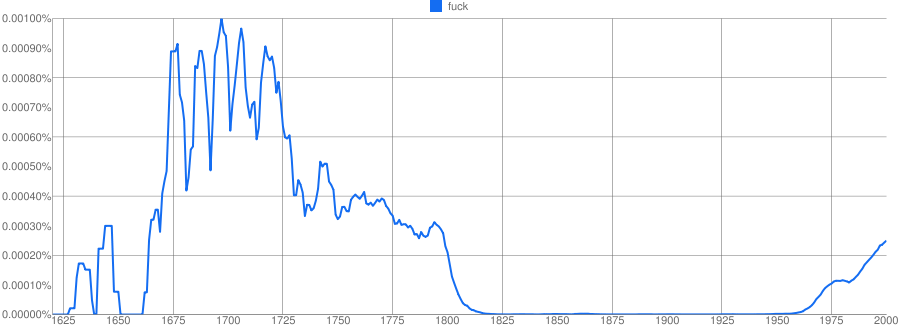

Of the words Cohen and Gibbs have chosen, one stands out as being more temporal than the others: revolution. None of the other terms is so event-related, or has a specific chronological location. Many are abstract, like ‘God’ or ‘honour’; some are names (‘Aristotle, ‘Jesus’, ‘Plato’ and ‘Socrates’); and there’s one place, Rome. That does not mean that there is no relation between these words and contemporary events – Rome has a startling peak in 1851, possibly related to the French occupation in the aftermath of 1848. Nor does revolution refer only to moments of uprising; it can equally mean the movement of the planets and the development of industry (Google’s ngram machine has the latter taking off in the 1880s). But it is the only chosen term that has a specific chronological collorary. Although the project is oriented around more long-term and subtle concerns, the changes in Victorian mentalities, I began to wonder how much the data reflected more immediate responses to human affairs.

Unsurprisingly, in the case of revolution, we have a mass of titles registering in the 1790s, and a very sharp peak in 1848. There are two other clear spikes in 1817 and 1830/1. A little bit of scrutiny, and you’ll see that 1871, the year of the Paris Commune, shows a marked increase. From prior knowledge of revolutions and threats of them, we can validate the data as reflecting events. As yet the statistics are not telling us anything new. There are some differences if one visualizes the data as the number of publications rather than percentages. 1830-1 and 1848 still stand out, 1817 and the Paris Commune less so. There also seems to be a different distribution: the last few decades have far more occurrences more evenly distributed than the first half of the century.

Graph of no. of English books published 1789 - 1914 with 'Revolution' in the title

Although it is important to check the data against what is already known, one must guard against presumptions of correlation. Can we be sure we know what revolution is being reflected? 1848 saw revolutions throughout Europe, but were the titles referring to all of them, a subset, or even just the domestic radicalism of the Chartists? Similarly, Cohen considers the 1830 spike to point to “the successful 1830 revolution in France”; but given the figures for 1831, it could be a result of the turmoil preceding the reform act of 1832. Merthyr Tydfil saw perhaps the first industrial working class uprising in Britain; Bristol and Nottingham saw state institutions go up in flames; there were incidents across the country, from Exeter to Huddersfield. The British publishing trade may have taken more note of this than three glorious days in Paris: the small rise around 1871 may also indicate that British publishing would register domestic concerns far more dramatically than events abroad. Against this, the jump in 1857 is probably due to the Indian Mutiny. In turn, the 1831 figures could indicate that the situation in Britain was far more volatile than todays historians have judged it.

So although there is evidence of a causal relationship between events and book titles, it is not transparent. It is further clouded by changes in the meaning of the word. The sustained increase over the last 25 years suggests a change in the conception of revolution from taking to the streets to building working class organizations, from riot and insurgency to factory strikes and the new unionism, from an immediate event to a longer term social struggle. This indicates a fundamental change in class structure – the growth of an industrial proletariat – and consistent class antagonism. But note that events still affect the numbers: the increase from 1904 to 1905 is probably due to the first Russian revolution.

The greater concern with domestic events and the change in meaning of the word ‘revolution’ are working hypotheses. Hopefully, the full corpus from which the numbers are drawn will be opened up, allowing these to be checked. I’d also like to investigate the 1853 spike, after the defeat of the Chartists and with no foreign correlate that I can think of.

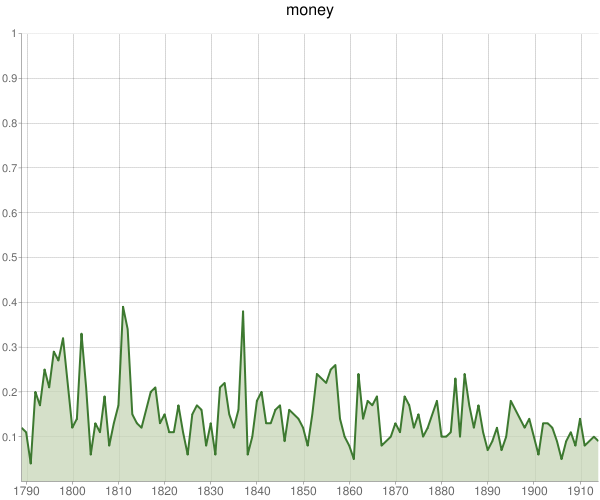

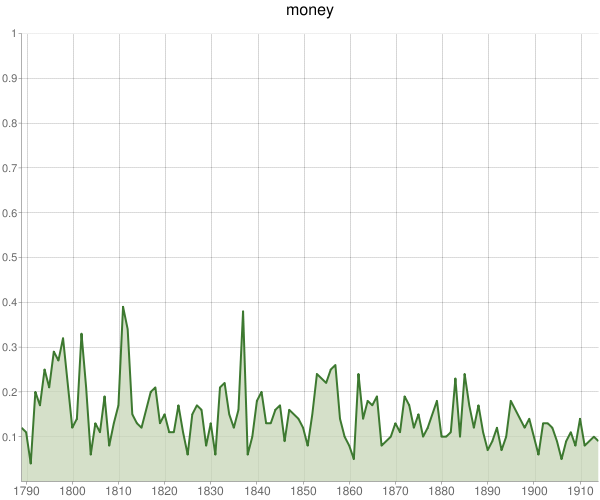

Finally, a curious absence, and a warning against presuming an easy reflection of reality in words. The following graph is of the occurrence of the word ‘money’ in book titles, expressed as a percentage.

Percentage of British books with 'money' in the title, 1789-1914

See that dip for 1825? Yet there was a banking crisis that year!

* Insert standard complaint about proprietary file formats here. However, it’s a simple spreadsheet, and neither Open Office nor Libre Office had any difficulties opening it.