A couple of Fridays ago (6th May 2011) I attended the Luddites Without Condescension event at Birkbeck. What I took away:

1: The Luddites are politically charged. The word is commonly used today as a slur to anyone questioning modern technologies. The impetus behind many of the commemorations is coming from activists involved in campaigns against the likes of genetically modified foods and cloning. This isn’t an academic or antiquarian history.

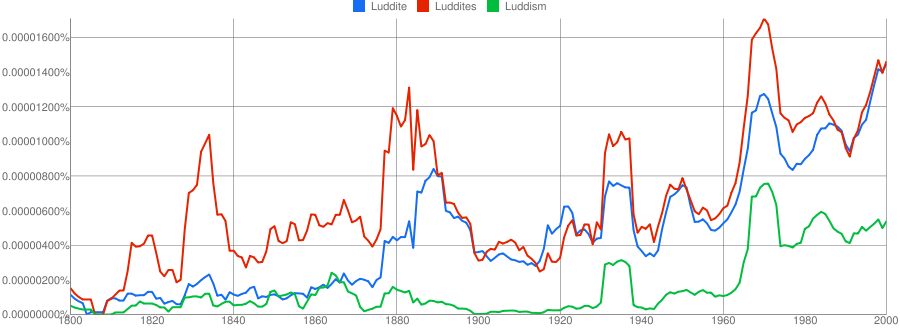

2: The word has a history. This was brought up by one of the audience in the midday discussion session, which had me reaching for my ngrams:

The remarkable aspect of this graph is that it shows four periods of sustained use of the terms Luddite and Luddites after the initial movement subsided. The late 1960s peak can be understood as part of the rising green, ecological movements, and the 1830s due to Captain Swing, but I can’t see easy explanations for the other periods. Perhaps the 1880s relates to the ‘new unionism’, and the 1930s the great depression and a corresponding lack of faith in progress. The 1930s also see the first concerted use of the term ‘Luddism’, as a theorization of their practice. There’s also a jump in the late 1940s; a consequence of Hiroshima and Nagasaki perhaps? One of the problems of this data is it’s not clear who is using the word, or how; is it a smear thrown at one’s enemies, or a claiming of one’s own tradition? (The results pre-1810 are due to Google’s dodgy metadata.)

3: There’s a history of rocketry that predates – and subverts – that of Wernher Von Braun. Peter Linebaugh mentioned the early uses of rockets as weapons, by the Kingdom of Mysore against the East India Company in the late eighteenth century. They were then taken up by the British military, and used for signaling as well as for artillery. States one account of the Luddites:

In some instances, signals were made by rockets and blue lights, by which they communicated intelligence to the parties, and the system evinced an extraordinary degree of concert, secrecy and organization.

This quite confuses the traditional view of the Luddites as being indiscriminately against all technology. There’s judicious adoption of modern communications here!

4: Peter Linebaugh needs to write about his historiography. I felt his talk, rich though it was, full of anecdote and story, didn’t come together. From the Comet of 1811, via a couple of earthquakes, Indian and Slave revolts, enclosures (133 bills passed in 1811), grain exports from Egypt to the Peninsular army, an Irishman searching for a teacher of classics, ballooning and Bardology, to Queen Mab by Shelly and the Ratcliffe Highway murders, it was always suggestive but more jigsaw pieces than a well-woven tapestry. Yet it wasn’t a random assemblage; a theme of global cotton – grown in India and America, worked up in England by machine and worker – was starting to emerge. Linebaugh made mention of his technique as ‘pulling at a thread’, but that isn’t explicit enough a description for what he does

5: Were the Luddites successful? Iain Boal made an important point about what success means. Just putting off mechanization for a generation, to safe-guard the livelihoods of weavers, is a victory (of sorts).

The talks were recorded by the Backdoor Broadcasting Co., and are available now. Meanwhile, follow the Luddite Bicentenary blog and Luddittes 200.